It took Molly a couple years to convince me to ride in the Riverwest 24 Hour Bike Race. Sitting on her balcony in the twilight over our glasses of red wine, Molly always made the event sound appealing for its sense of community and the unique twist of a tattoo that many riders get to commemorate their participation — a grittier, gutsier step beyond “been there, done that, got the t-shirt.”

The more Molly talked about the ride through the Riverwest neighborhood of Milwaukee, the more it sounded like a dare, the mix of athletic challenge and encouragement we’d shared since high school. But now we were 60, and the prospect of bicycling for 24 hours and getting a tattoo seemed absurd.

“You don’t necessarily ride the whole 24 hours,” Molly explained. “You get off the bike for checkpoints, where you can drink a beer or have a community experience in one of the shops or in people’s homes. Some people sleep or trade off shifts with their teammates. It’s not competitive.

“And, you don’t have to get the tattoo” she said with a smile that looked more 16 than 60. “But you know you want to.”

OK. Sold. Which is how we got here.

At the start just in front of Molly, backed by (L. to R.) Maureen, Carol, Brenda, and Colleen, members of Team Millio Zillio.

In the seconds before the 7 p.m. start of the Riverwest 24 on July 26, 2024, roughly 1,800 registered riders are a mass of nervous energy, ringing bells to signal they’re ready to roll.

At the start, cyclists surge forward. Then they stop. The crowd condenses. Sardined in the street with at least 1,800 riders of various ages, abilities, and levels of patience and competitiveness, it suddenly seemed a lot could go wrong. Less than a week after Milwaukee hosted the Republican National Convention, hair trigger tempers remained as hot as the air temperature.

Plus, the Riverwest 24 coincided with the Milwaukee Air & Water Show, featuring the U.S. Air Force Thunderbirds, and the Harley-Davidson Homecoming, bringing thousands of riders new to Milwaukee’s streets, who were bound to be frustrated by bicycle traffic. The threat and promise of sonic booms and backfires jangled nerves.

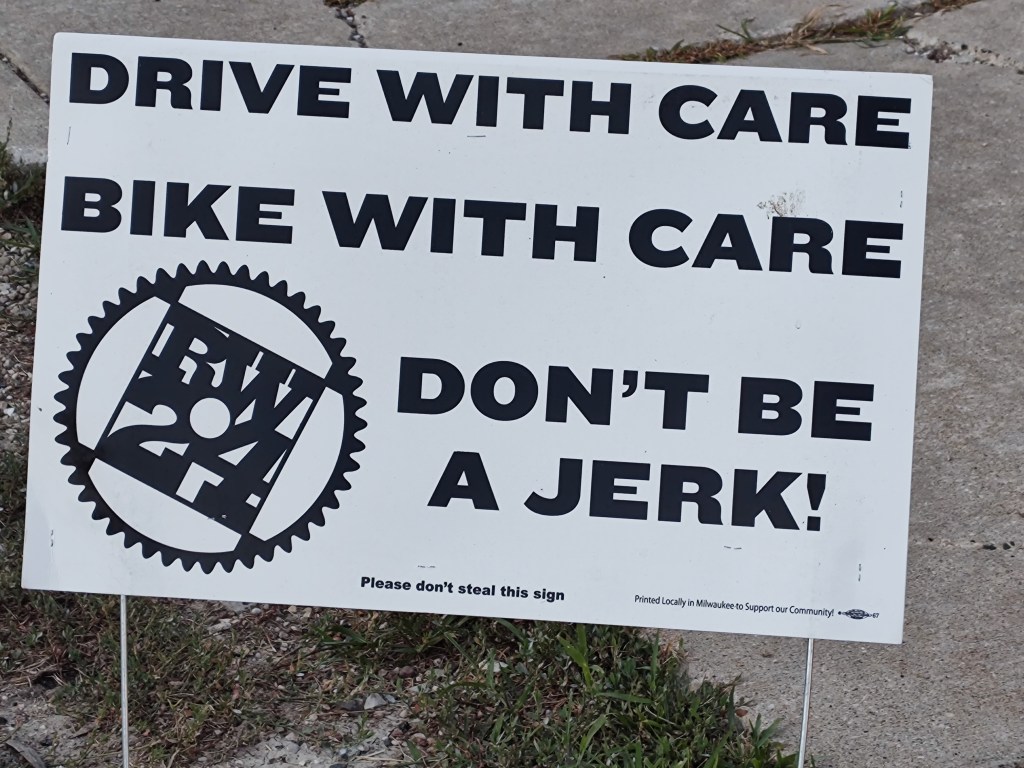

With scant police presence assigned to our ride, our community would police itself. Fortunately, Riverwest 24 organizers guided us with simple reminders.

Gradually, riders spread throughout the 4.6 mile course. Speedsters sped. We in the “Elder” category that Molly signed us up for did not.

Instead, we enjoyed high-fiving the little kids lining the residential streets in front of their parents’ homes or shade tents standing curbside. We basked in their cheers and encouragement, laughed at humorous handmade signs, and admired artwork scattered throughout the route.

Occasionally, we stopped at “bonus checkpoints” to get our “passports” stamped, earning points in addition to those for each completed course lap.

The bonus checkpoints brought us into homes, businesses and parks, where we participated in cleverly named non-cycling activities. For example, “Don’t Pull a Hammy” provided a stretching session inside the cavernous Dropout Fight Club boxing gym, and “Let the Rhythm Move You” at Wu-Tang Park offered a group belly dancing lesson.

From about 9-11 p.m., we took a break from our bikes to watch a street circus from Molly’s balcony.

Then, just Carol and I ventured back out for more laps and checkpoints. The laps led us past pulse-pounding street parties, live bands, DJs, drunken revelry, and all the rest of the eclectic energy that marks the Riverwest community.

My favorite checkpoint was “A Night at the Museum” in the Jazz Gallery Center for the Arts, housed at the old Jazz Gallery performance space, where, as a high school senior, I watched Art Pepper play alto just weeks before he died. While Carol perused the Riverwest 24 memorabilia display, I got lost in the jazz artifacts and a recording of the late great Milwaukee jazz radio DJ Ron Cuzner and was transported back to 1982.

Other checkpoints reflected the quirkiness of the Riverwest community. “What Are You Buying? What Are You selling?” featured a masked and hooded man inside a candle-lit tent on the Beerline bicycle trail, who mutely helped us discern how to complete a transaction for a vial of “potion” that turned out to be an ounce of kombucha. In someone’s basement we threw darts at balloons for a chance to win a container of Cup Noodles ramen. By 2:30 a.m., I needed off the streets with about 23 miles behind me.

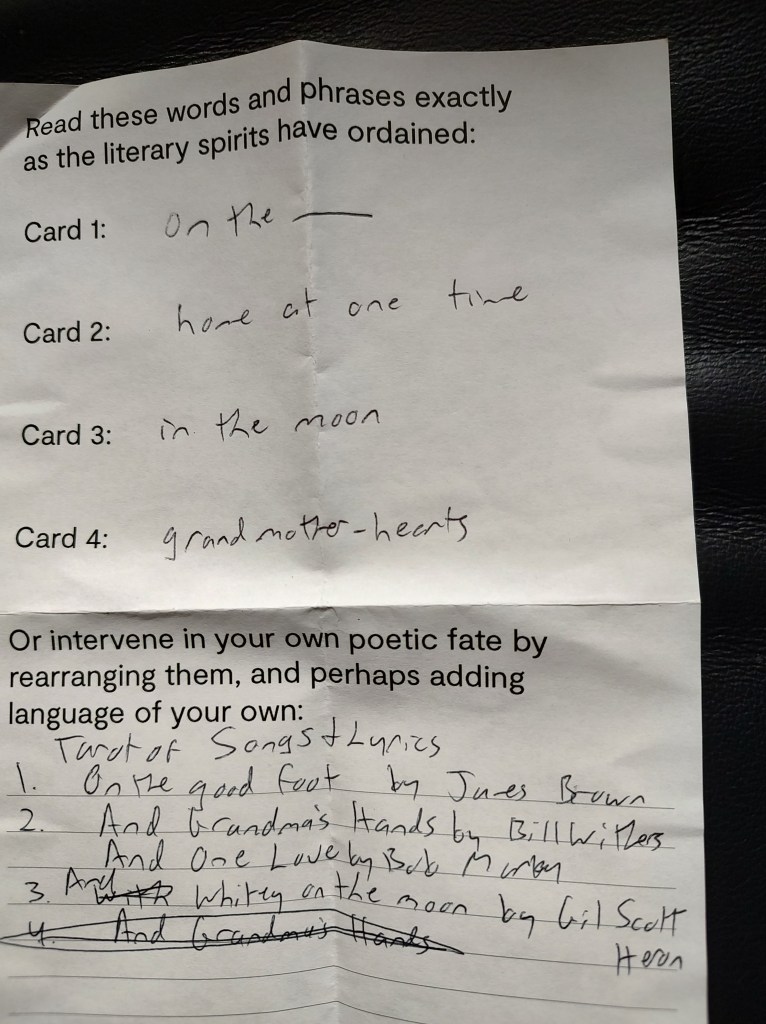

I slept from 3-6 a.m. By 7, I was back out on the bike for the day’s first bonus checkpoint. “Poetry Tarot” occurred at Woodland Pattern, an independent bookstore that sells my book Az Der Papa. To get my passport stamped, I sat for a turn of tarot cards with random phrases that I was told to transcribe, edit into a new piece of writing, and read aloud on the mic to whoever was in the street.

Our Team Millio Zillio group text re-convened us at Woodland Pattern, where we planned a strategy to help our team complete a total of 20 laps before the race ended 12 hours later. Through a comedy of flat tires, needing to meet teammates’ delightful adult children at various checkpoints, and wanting a traditional Milwaukee brunch of Bloody Mary, we rode — sometimes alone and other times together — until an appointed stop at “The Pride of Milwaukee” checkpoint, which opened at noon at Black Husky Brewing.

Damn good Bloody Mary served Wisconsin style with a chaser of pilsner brewed onsite and damn fine company as we ran into old high school buddy Mike D’Amato (not pictured).

From there, we ground through laps to get our goal in the 82-degree heat, amid the cacophony of Harleys and Air Force jets, surrounded by swarms of competitive cyclists. We were sleepy and sore, but fueled by free food at one of the checkpoints and soaked in sweet relief by sprinklers and squirt-gun toting curbside kids. The Riverwest community rallied around us and kept us going.

By about 6 p.m., we finished our 20th lap. Riverwest 24 officials at the final checkpoint punched the last hole in the second page of our official race manifest.

We rode to our 6:30 tattoo appointments at Falcon Bowl, established 1915. We waited at the bar, replenishing our precious bodily fluids and building our courage until it was time to climb the narrow staircase in stifling heat to an office space/tattoo parlor. For about five minutes and with minimal pain, we permanently commemorated our ride, earning the bonus points that put us in a 7th-place tie on the leaderboard among 19 teams in the Elder category.

Our most important business complete, we rode back to the finish line, just as the race officially ended, satisfied with these stats.

We sat on the patio of Club 99, watching people take turns launching their bikes off the ramp at the Cheese Jump.

Over our last beers of the Riverwest 24, we swapped stories of our own adventures and gratitude for the community commitment it took to manage 1,800 riders and untold numbers of spectators, from the top echelon of organizers to each and every volunteer pool noodler who directed traffic over the previous 24 hours, keeping us safe, sane, and supremely satisfied with our experience.